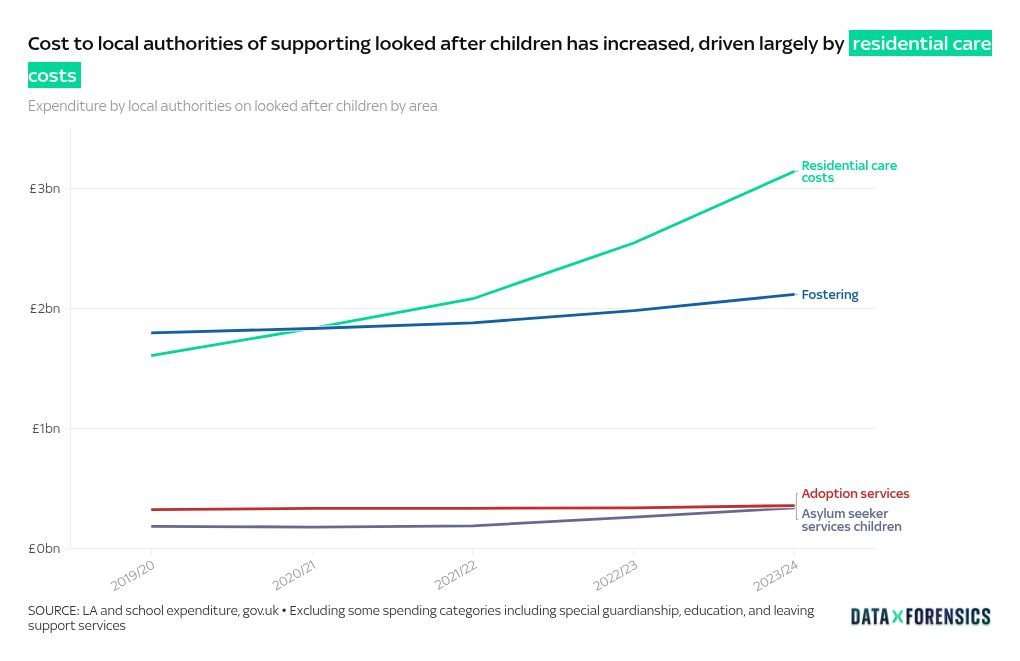

The annual cost of children’s residential care has almost doubled to £3.1bn since 2019, putting pressure on local authority finances.

The focus of the National Audit Office report is to evaluate the Department for Education’s (DfE) response to the challenges facing local authorities, which have a duty to place looked after children.

Its conclusion is that the system isn’t providing value for money, with inadequate government oversight and lack of data contributing to the issue.

One in seven children in residential care were moved home at least twice over the course of a year, as of the latest data for March 2024.

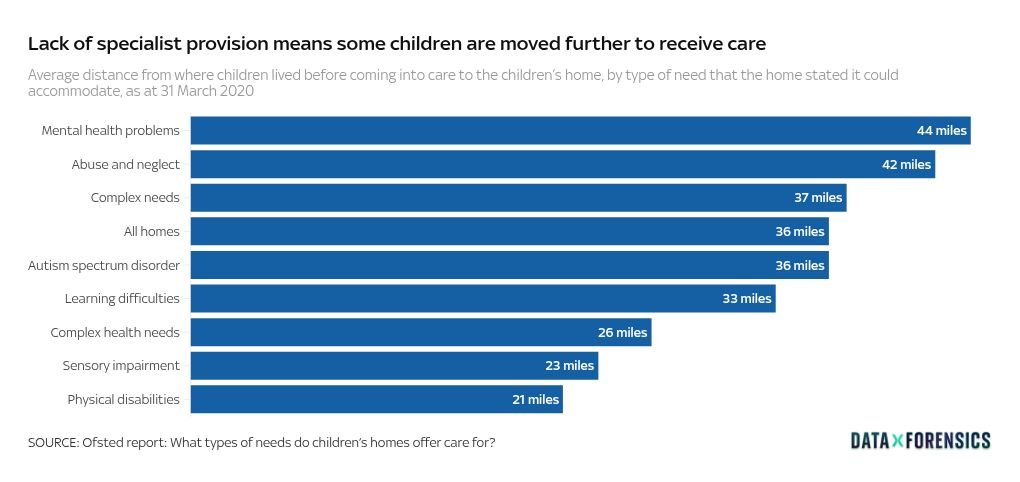

And nearly 8,000 children in residential care in England are now placed more than 20 miles from their original family home.

There are regional differences in supply affecting the availability of places, with more homes in cheaper areas such as the north west, while three in five children in the south west are placed far from home.

«Our main concern is that children are not being supported in the most appropriate setting for them. That will impact outcomes for them,» Emma Willson, NAO director of value for money in education, told Sky News.

The report highlights that looked after children already face numerous challenges – two in three have a history of abuse and neglect, and those leaving care are three times more likely not to be in education, training, or employment than their peers.

«For the department [DfE] to better fulfil its role overseeing the sector, it needs to build better information on both the supply and the availability of places, but also on the children’s needs for those places to be able match,» Ms Willson, who was lead author of the report, said.

The distribution of homes that can support specific needs varies significantly, with fewer than 10% of homes in London able to support children with complex needs including autism and learning difficulties, as of the latest snapshot from 2020.

A previous Ofsted report, published in 2022 found that 80% of children living in children’s homes had special educational needs, much higher than the 52% of all looked after children and 15% of all children.

Providers are responsible for staff recruitment and training so they can meet the needs of children in their care.

However, the lack of suitable settings for children with complex needs means they are moved further from home as a result.

Pressure on funding

In recent years, the availability of foster placements has decreased, which the DfE suggests is due to wider economic pressures and housing shortages.

Overall, spending on looked after children has increased by almost £3bn to £8.1bn from 2019/20 to 2023/24. The increase in spending on residential care contributed to more than half of increased spending.

This is because local authorities have become more reliant on residential care, with 16,510 children in residential care in March 2024, an increase of 10% from 2020.

A limited number of places for those children has resulted in a «dysfunctional market» where local authorities compete for places resulting in increasing costs.

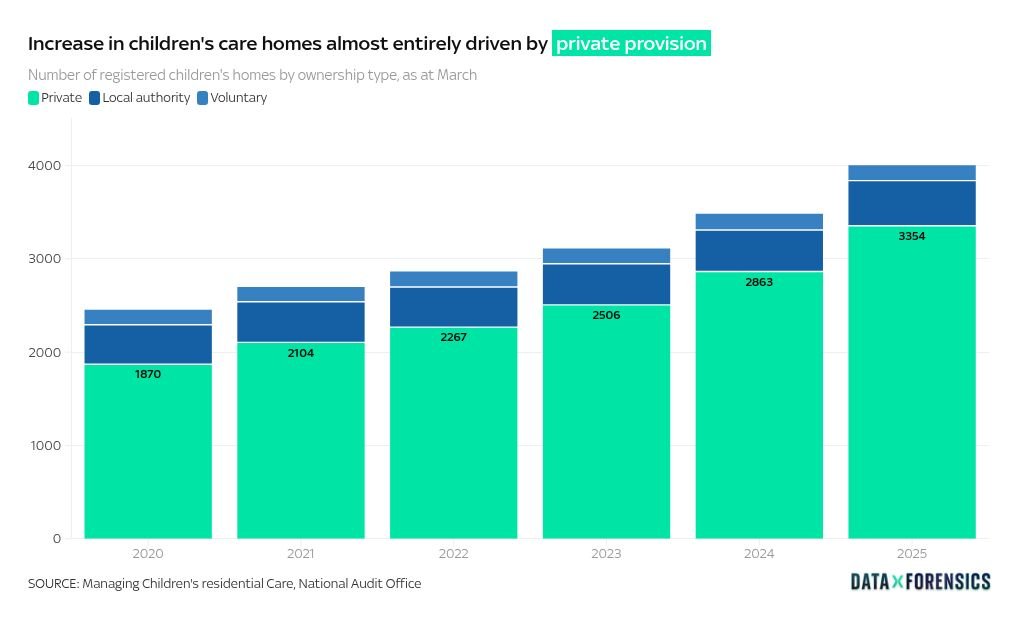

Most of the increase in overall number of residential providers is in the private sector, rather than through local authority or voluntary provision, and private provision now accounts for 84% of the market, increased from 76% five years ago.

Though the number of homes has increased by 63%, the government does not hold data on how many places are available by provider, Ms Willson said.

Barriers to opening new homes include staff shortages, high property prices, and difficulty securing planning permission.

The average spend per child for a private residential placement in 2023/24 was £318,400 – an increase of 32% in real terms from £239,800 in 2019/20, while cases have been identified where costs are more than 10 times as high.

A separate report from 2022 by the Competition Markets Authority found above expected profits.

The 15 largest private providers were estimated to have average profit rates of 22.6% for children’s homes from 2016 to 2020, with prices increasing above inflation. Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown, chair of the Committee of Public Accounts, referred to the rising costs of residential care as a strain on local authority finances, calling the market «dysfunctional.» Lack of coordinated commissioning, insufficient planning, and supply-demand mismatches were identified as factors fueling this dysfunction. Local authorities have resorted to unregistered providers, with reports showing that at least 86% of them have used such care. In 2023/24, 982 children were confirmed to be placed in unregistered children’s homes, a nearly sixfold increase from 2020/21. Only 6% of unregistered providers applied for registration after receiving a warning letter, and out of those, only 8% were approved. The Children’s Commissioner found that 31% of children in unregistered placements were subject to deprivation of liberty orders in December 2024. The Department for Education (DfE) plans to invest £508m in capital funding to create around 640 additional places in children’s homes by 2029. However, the DfE lacks the necessary data to identify reasonable prices for residential care homes or excessive profits. Emma Willson, NAO director of value for money in education, stated to Sky News that this will have an impact on outcomes for looked after children. The report emphasizes the challenges faced by these children, with two in three having a history of abuse and neglect. Those leaving care are three times more likely to not be in education, training, or employment compared to their peers.

Ms. Willson, the lead author of the report, mentioned that the Department for Education (DfE) must improve its oversight by gathering better information on the supply and availability of places, as well as understanding the needs of children to ensure a match. The distribution of homes that can support specific needs varies greatly, with a limited number of homes in London equipped to support children with complex needs like autism and learning difficulties.

The report also revealed that there has been a decrease in foster placements due to economic pressures and housing shortages. Spending on looked after children has increased significantly, with residential care accounting for more than half of this increase. The reliance on residential care has led to a competitive market among local authorities, resulting in rising costs.

Despite an increase in the number of homes, data on available places by provider is lacking. Barriers to opening new homes include staff shortages, high property prices, and difficulties with planning permission. The cost per child for a private residential placement has increased substantially, with cases showing costs more than 10 times higher than average.

The report highlights the need for the DfE to take more decisive actions to ensure children receive appropriate care at the right cost. Local authorities resorting to unregistered providers has also raised concerns, with a significant increase in children placed in unregistered homes. The report suggests that more needs to be done to address these issues and ensure that children receive the care they need. Ms Willson emphasized that without the necessary data, the Department for Education cannot accurately assess whether its capital investments are being allocated effectively to provide adequate support for children. She highlighted the lack of information hindering the identification of reasonable pricing for residential care homes and the detection of excessive profits within the sector.

The National Audit Office’s report sheds light on the escalating annual cost of children’s residential care, reaching £3.1bn by 2019, which has strained local authority budgets. The report scrutinizes the DfE’s response to the challenges faced by local authorities in placing looked after children, concluding that the system is failing to deliver value for money due to insufficient government oversight and data deficiencies.

Disturbingly, one in seven children in residential care experience multiple relocations within a year, with nearly 8,000 children in England residing over 20 miles away from their original homes. Regional disparities in care availability compound the issue, with disparities in homes distribution affecting accessibility. For instance, the south west has a higher proportion of children placed far from home compared to the north-west.

Emma Willson from the NAO emphasized the detrimental impact of children not receiving appropriate support in suitable environments, affecting their overall outcomes. She stressed the importance of the DfE improving its oversight by enhancing data on both care supply and demand to ensure better matching of resources to children’s needs.

The distribution of care facilities for children with specific needs varies significantly, with London having fewer than 10% of homes capable of supporting children with complex needs like autism and learning difficulties. The prevalence of special educational needs among children in residential care is alarmingly high, as highlighted in a 2022 Ofsted report.

The report underscores the challenges faced by providers in recruiting and training staff to meet the diverse needs of children in their care. However, the shortage of suitable facilities for children with complex needs leads to further displacement from their original homes.

Financial pressures have exacerbated the situation, with foster placements becoming scarcer due to broader economic constraints and housing shortages. Total expenditure on looked after children has surged to £8.1bn, with a significant portion allocated to residential care, driving up overall costs.

The rise in spending on residential care has intensified local authorities’ reliance on such facilities, resulting in a competitive market where costs escalate as authorities vie for limited spaces. Private sector expansion has dominated the market, accounting for 84% of providers, up from 76% in the past five years.

Despite a 63% rise in the number of care homes, the government lacks comprehensive data on available places per provider. Challenges in opening new facilities include staffing shortages, high property prices, and planning permission hurdles. The average cost per child for private residential placements has surged by 32% in real terms, with instances of costs exceeding tenfold.

Additionally, a 2022 report by the Competition Markets Authority flagged unexpected profits in the sector. These findings underscore the urgency for the DfE to address the systemic deficiencies and data gaps to ensure better outcomes for looked after children. Between 2016 and 2020, the 15 largest private providers in the children’s homes sector had an average profit rate of 22.6%, with prices rising above inflation. Sir Geoffrey Clifton-Brown, chair of the Committee of Public Accounts, referred to the escalating costs of residential care as a burden on local authority finances. He described the market as dysfunctional due to lack of coordination in commissioning, inadequate planning, and mismatches in supply and demand leading to increased prices. The Department for Education (DfE) has taken some steps to improve the residential care market but must do more to ensure children receive appropriate care at reasonable costs. Local authorities have resorted to using unregistered providers, with reports indicating that 86% of authorities have utilized such care. The number of children placed in unregistered homes has significantly increased, prompting concerns about their well-being. The Children’s Commissioner found that a significant percentage of children in unregistered placements were subject to deprivation of liberty orders. Recommendations for improvement include increased capital funding for additional children’s home places. However, the DfE lacks necessary data to assess the effectiveness of these investments and to identify reasonable costs for residential care.

SOURCE